Politically, Szőnyi was as moderate as he was artistically, and in this he typified Hungarian artistic life of the period between the wars. Although he was more than familiar with the Hungarian avant-garde artists and their work, he made a conscious decision not to emulate their pictorial and political strategies, but rather to forge an intermediate style requisite to his subject matter. Instead of the traditional religiosity promoted by the interwar Hungarian government, it was a kind of pantheistic understanding of the relationship between humanity and the land that makes itself felt in Szőnyi’s oeuvre. This opening to the land was Szőnyi’s opening to the world. His turning inwards, on the other hand, was a turning towards the private sphere of family and friends, including a number of artist friends who spent shorter and longer periods of time at his summer place (later his home) at the village of Zebegény in the Danube Bend area. Among the artists affected by Szőnyi’s artistic stance and approach during the early 1920s were Vilmos Aba-Novák, Károly Patkó, Erzsébet Korb, and the photographer André Kertész. Following Gauguin and classicizing avant-garde artists such as Béla Uitz and József Nemes-Lampérth, these artists tried to locate in their work a kind of ideal rural utopia, an “Arcadia,” as art historian András Zwickl has put it. This Arcadia was rooted in rural values, the Hungarian landscape, and the peasantry. While Szőnyi went to Italy in 1924, and returned there in 1929 on the Hungarian government Prix de Rome scholarship, Italy did not captivate him the way it did his contemporaries such as Aba-Novák and Patkó. His “Italy” was the Danube Bend area north of Budapest, where he lived full time from 1924 to 1930. By the 1930s, his softer Neo-Impressionist painting and graphic arts style had become one of the formative elements of what became known as the “Post-Nagybánya” style of the prominent “Gresham Circle” of artists that included Aurél Bernáth and Ödön Márffy. In 1937 he was appointed to a professorship at the Academy, and he subsequently became influential as a teacher. It was at this point that he became, in a sense, a kind of “official” artist of the regime. One of the most important (if late) examples of Szőnyi’s “Arcadia” mode of painting is the monumental work Aratás [Harvest], based on his wall mural for the Hungarian Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair of 1937. Szőnyi then represented Hungary with Aratás at the exhibition of “Contemporary Art of 79 Countries” at the Golden Gate International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1939. Though beautifully rendered, its idealized visions of the peasantry – understandable given its origins in international exhibitions organized by the Hungarian government – avoided real issues facing the country’s rural population, including widespread poverty and landlessness. In any case, “Harvest” was acquired from the Golden Gate show by the IBM corporate collection, and was subsequently lost to view. It was acquired by the Salgo Trust from the important New York collector and dealer of Hungarian art, Michael Szarvasy and was shown for the fist time since 1939 in “Calm Before the Storms: István Szőnyi and Hungarian Art Between the World Wars” at the American Hungarian Foundation in 2004. (OB)

István Szőnyi (1894–1960)

A művek listája

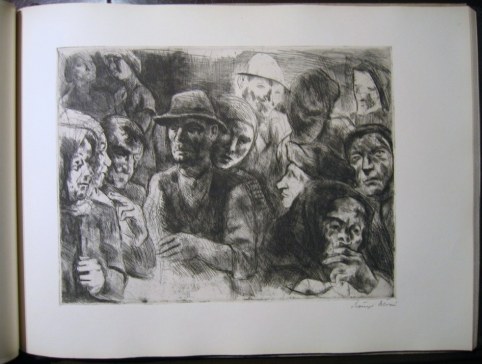

If anyone was, István Szőnyi was the paradigmatic Hungarian artist of the interwar period. He studied with Károly Ferenczy at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts before the Great War, and with the more conservative professor István Réti after it. His war service was interrupted by brief periods at the Nagybánya artists’ colony in Transylvania. Despite his brilliance in the graphic arts, Szőnyi avoided studying at the Academy with the Theosophist Victor Olgyay, the founder of modern Hungarian graphic art. Rather, he turned to the work of Béla Uitz, a prominent member of the Hungarian avant-garde “Activist” group, as well as to Rembrandt, for inspiration. This album, produced at some point after World War II, is a remarkable assembly of Szőnyi’s essays in chiaro-scuro of the 1920s and early 30s. It represents the full range of Szőnyi’s graphic work, including landscapes, rural scenes of the peasantry and their life, sensuous nudes, a couple of religious scenes portrayed through representations of the peasantry, and even a historical scene or two. It is above all in the early works, especially those that depict his wife and child, that one senses the importance that Uitz’s graphic oeuvre of the teens held for his own development. This album, presented to the Salgo Trust by Dr. Miklos Salgo, executor of the Salgo Trust and son of Ambassador Salgo, represents some of the best work of that Hungarian fluorescence of graphic art, particularly etchings, that spanned the 1920s and garnered international success. (OB)